Reducing Mortality in the Opioid Epidemic: What is Miami Doing Differently from the Rest of Florida and the US?

Opioid-related mortality in the United States has soared in the past two decades. A combination of institutional shifts in approaches to pain management, widely publicized unscrupulous marketing and prescribing practices, and increases in the availability and heightened potency of illicit opioids has resulted in such broad loss of life that the US has seen a decrease in the national life expectancy two years in a row. The peak of the HIV/AIDS crisis resulted in a one-year drop in life expectancy in 1993, but a multi-year drop has not been seen since 1963, with the occurrence of the Hong Kong H3N2 influenza pandemic.

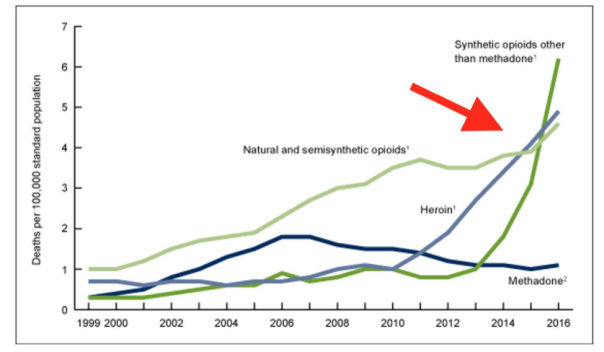

Age-adjusted drug overdose death rates by opioid category United States 1999-2016

Like many other states facing an opioid crisis, Florida has seen a profound increase in deaths caused by opioid overdose. Miami-Dade County, in particular, accounted for an outsized proportion of the mortality burden, accounting for 13% of the deaths associated with opioid overdose in the state in 2016. As noted by Jessica Lipscomb in the Miami New Times, “since 2011, the number of people who’ve died with heroin in their system grew from 56 to 1,023. Year over year, deaths caused by heroin increased 30 percent from 2015 to 2016.” The Florida opioid mortality curve closely mirrors that of the national opioid mortality statistics:

As Centers for Disease Control and Prevention statistics show, opioid overdose deaths were rising steadily along with national averages, until 2013, when the apparent mortality skyrocketed. But what changed?

In the case of Florida, two overlapping phenomena have played a major part in this public health emergency:

- Changes in laws that allowed for prosecution of unscrupulous prescribers, with a subsequent diversion of consumers to illicit drug sources

- Changes in illicit opioid consumption patterns from natural and semi-synthetic opiates like heroin and morphine to synthetic opioids

In 2011, Governor Rick Scott signed into law HB 7095, the “Pill Mill Bill” which declared the opioid epidemic a public health emergency and allowed the Statewide Drug Strike Force to begin shutting down namesake “pill mills.” By 2013, nearly two-thirds of so-called pill mills had closed. FDLE data shows the moment in 2013 when heroin began to overtake legal, prescribed opioids as the most frequent cause of opioid-associated mortality, and the data then again shows in 2016 when fentanyl and its analogs dwarfed even heroin in their lethality:

The anesthetic adjunct fentanyl has received the most attention, but recently, even more potent analogs and derivative synthetic opioids such as carfentanil and ocfentanil – previously found only in veterinary medicine – have been implicated in overdose deaths as well.

Fentanyl and its analogs are hundreds of times more potent than natural and semisynthetic opiates like heroin and have overtaken legal and other illicit opioids as a major contributor to mortality.

Fentanyl has crept into the illicit drug stream as heroin has become more scarce: the synthetic opioid was involved in nearly half of opioid-related deaths in 2016. There are many reasons for this, including that the continued Global War on Terror has disrupted both the underground drug trafficking economies that exported heroin as well as the natural opiate substrate of the heroin trade; opium poppy. In the place of the land- and labor-intensive crop, pharmaceutical laboratories in East Asia have contributed the lion’s share of illicit opioids entering the United States. Although fentanyl initially supplanted heroin, recent forensic and medical examiner reports have noted the opioid in a multitude of illicit drugs including those sold as cocaine, amphetamines and benzodiazepines. As Bode et al. (2017) note, “heroin users are unable to discern whether they have pure heroin or fentanyl/fentanyl-analog laced heroin”. While the dosages of fentanyl found in street drugs are dangerous for almost anyone, the risk of lethal toxicity is even higher in illicit drug consumers naïve to opiates.

In the face of this epidemic, one municipality in Florida has begun to turn the tide. Recent data from the Florida Department of Law Enforcement Medical Examiner Report demonstrated a 38.7% downturn in opioid-associated mortality in Miami-Dade County, the first such occurrence in half a decade. This drop was shared- albeit more modestly- by other counties in the vicinity of Miami Dade, such as Broward and Palm Beach counties.

As Molly Minta of the Miami New Times writes;

One possible reason is the University of Miami’s syringe exchange program. Green-lit in December 2016, IDEA Exchange is the only legal exchange program operating in the state of Florida…The program has distributed more than 1,000 doses of naloxone, an overdose-reversing drug. The evidence of a drop in opioid deaths is firm. The first six months of 2017 saw 177 fewer deaths due to heroin, fentanyl, and morphine use than the last six months of 2016.

The IDEA Exchange came into existence on the heels of Surgeon General Vivek Murthy’s report emphasizing the importance of needle exchange programs and began distributing naloxone nearly a year before Surgeon General Jerome Adams called for the widespread availability of the overdose reversal agent. Prior to the IDEA Exchange opening in Miami, naloxone was only available to EMS and hospitals – who have been using escalating quantities of the drug. Bode et. al (2017) determined that the safety-net hospital in Miami Dade County, Jackson Memorial Hospital, saw the number of opioid overdose cases present to the ED increase by 119% between 2015 and 2016, with a disproportionate 476% increase in naloxone use.

Naloxone was previously only available to professional rescuers and hospital providers but is now available to participants at the IDEA Syringe Exchange Program

The increase in number and severity of overdose was likely attributed to fentanyl and analogs becoming the major driver of overdose events. Similarly, the City of Miami Fire Rescue saw an eleven-fold increase in naloxone use from 2013-2016, from 400 to 4500 doses. But while EMS calls and ED presentations of overdose have increased, so has mortality in that timeframe. The traditional public health responses were only treading water in a tide of lethal opioids, until 2017, when the IDEA Exchange began naloxone distribution.

The approach of delivering naloxone directly into the hands of people who inject drugs (PWID) is not new. Seal et al. (2005) describe a 2001 trial in a CDC-cited report “Naloxone Distribution and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Training for Injection Drug Users to Prevent Heroin Overdose Death: A Pilot Intervention Study.”

This pilot is the first in North America to prospectively evaluate a program of naloxone distribution to IDUs to prevent heroin overdose death. After an 8-hour training… study participants’ knowledge of overdose prevention and management increased, and they reported successful resuscitations during 20 heroin overdose events. All victims were reported to have been unresponsive, cyanotic, or not breathing, but all survived. These findings suggest that IDUs can be trained to respond to heroin overdose by using CPR and naloxone, as others have reported.

To date, the IDEA SEP has delivered over 3000 doses of naloxone to the nearly 1000 program participants. Approximately half of the doses have been returned; demonstrating their use. Putting the reversal agent into the hands of PWID empowers those most likely to witness an overdose with the knowledge and tools to ameliorate the lethal effects of fentanyl in the critical moments just after drug consumption. The Miami example represents one of the largest ever examples of an application of opioid overdose public health interventions and demonstrates the quality of an effective initiative put into practice. While it remains to be seen whether the mortality benefit will bear out into the future, the Miami case is one to watch.

Report by Kasha Bornstein, MSPharm